Chapter 2: The Olympians

Previous Page Table of Contents Next Page

♦ Dresden, Albertinum 350: Attic red-figure calyx krater with Persephone, Hermes and Silenoi

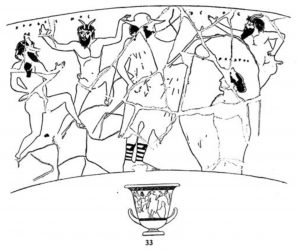

P. Herrmann, “Erwerbungen der Antikensammlungen in Deutschland,” Archäologischer Anzeiger 1892, 166 fig. 33

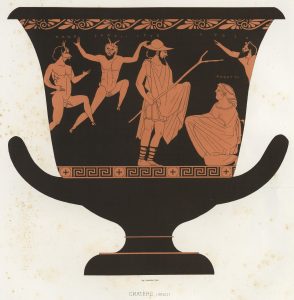

N. Des Vergers, L’Étrurie et les Étrusques: ou, Dix ans de fouilles dans les Maremmes toscanes, vol. 3 (1862-64), pl. 10

Beazley Archive Pottery Database

♦ Berlin, Antikensammlung 3275: Attic red-figure calyx krater with Persephone, Hermes and Silenoi

P. Hartwig, “Die Wiederkehr der Kora auf einem Vasenbilde aus Falerii,” Mittheilungen des Kaiserlich Deutschen Archaeologischen Instituts. Römische Abteilung 12 (1897), pls. 4-5

Beazley Archive Pottery Database

♦ Ferrara, Museo Nazionale di Spina 3031: Attic red-figure volute krater by the Painter of Bologna 279, with Persephone and Silenoi

Beazley Archive Pottery Database

♦ Stockholm, National Museum 6: Attic red-figure bell krater from the Polygnotos Group with Persephone and Silenoi

Annali dell’Instituto di Corrispondenza Archeologica 2 (1830), pl. K

Beazley Archive Pottery Database

♦ Paris, Cabinet des Medailles 298: Attic lekythos, Persephone and Silenoi

Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum. France 10: Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale (Cabinet des Médailles). Fascicule 2 (1931), pl. 85

Beazley Archive Pottery Database

♦ Oxford, Ashmolean Museum V525 (G275): Attic red-figure volute krater with Zeus, Hermes, Epimetheus, Pandora and Eros

Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum: Oxford, Ashmolean Museum. Fascicule I (1927), pl. 21

Percy Gardner, “A New Pandora Vase,” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 21 (1901), pl. 1

Beazley Archive Pottery Database

♠ Pausanias 8.25.4

After Thelpusa the Ladon descends to the sanctuary of Demeter in Onceium. The Thelpusians call the goddess Fury, and with them agrees Antimachus also, who wrote a poem about the expedition of the Argives against Thebes. His verse runs thus:—“There, they say, is the seat of Demeter Fury. Greek Text

♠ Kallimachos Hymn 6 to Demeter – Callimachus 2, pp. 35-40, ed. R. Pfeiffer. Oxford 1953.

♠ Hesiod, Ehoiai (Catalogue of Women) fr 43a1-11 MW – Fragmenta Hesiodea, pp. 27-31, ed. R. Merkelbach and M. L. West. Oxford 1967.

[. . .pre]tty-crowned Polymele. [Or like the daughter of] god[like Erysichthon . . .] of the [. . .] son of Triops, [Mestre of pretty locks,] who had the [s]parkles [of the Graces; and they called him Aithon by] n[a]m[e] because [a blazing, mighty] famine [. . . the tribes] of mortal humans [. . .] and all [. . . blazi]ng famine [. . . for m]ortal humans [. . .] kn[ow- . . . shre]wd counsel in their [h]earts [. . . of w]omen [. . .] (Transl. Silvio Curtis)

♠ Hellanikos 4F7 – Die Fragmente der griechischen Historiker 1, p. 109, ed. F. Jacoby, 2d ed. Leiden 1957.

♠ Palaiphatos 23 – Mythographi Graeci 2, pp. 31-32, ed. N. Festa. Leipzig 1902.

Mestra: About Mestra the daughter of Erysichthon, they say that whenever she wished she could change her shape. The myth is laughable. How likely is it that from a girl she could become a cow and again a dog or bird? The truth is thus: Erysichthon was a Thessalian man, who went through his money and became poor. He had a daughter, the good and beautiful Mestra. Whoever saw her was amorously disposed. People then did not get betrothed with silver coin but instead some gave horses, others cows, some sheep or whatever Mestra wanted. The Thessalians said, seeing the livelihood of Erysichthon piling up, “From Mestra came horse and cow and other things,” whence the myth developed. Greek Text

♠ Lykophron, Alexandra 1391-96

him who of old was utterly hated by the goddess Cyrita: the father of the crafty vixen who by daily traffic assuaged the raging hunger of her sire – even Aethon, plougher of alien shires. Greek Text

♠ Ovid, Metamorphoses 8.738-878

ERYSICHTHON AND MESTRA

Now Erysichthon’s daughter, Mestra, had

that power of Proteus—she was called the wife

of deft Autolycus.—Her father spurned

the majesty of all the Gods, and gave

no honor to their altars. It is said

he violated with an impious axe

the sacred grove of Ceres, and he cut

her trees with iron. Long-standing in her grove

there grew an ancient oak tree, spread so wide,

alone it seemed a standing forest; and

its trunk and branches held memorials,

as, fillets, tablets, garlands, witnessing

how many prayers the goddess Ceres granted.

And underneath it laughing Dryads loved

to whirl in festal dances, hand in hand,

encircling its enormous trunk, that thrice

five ells might measure; and to such a height

it towered over all the trees around,

as they were higher than the grass beneath.

But Erysichthon, heedless of all things,

ordered his slaves to fell the sacred oak,

and as they hesitated, in a rage

the wretch snatched from the hand of one an axe,

and said, “If this should be the only oak

loved by the goddess of this very grove,

or even were the goddess in this tree,

I’ll level to the ground its leafy head.”

So boasted he, and while he swung on high

his axe to strike a slanting blow, the oak

beloved of Ceres, uttered a deep groan

and shuddered. Instantly its dark green leaves

turned pale, and all its acorns lost their green,

and even its long branches drooped their arms.

But when his impious hand had struck the trunk,

and cut its bark, red blood poured from the wound,—

as when a weighty sacrificial bull

has fallen at the altar, streaming blood

spouts from his stricken neck. All were amazed.

And one of his attendants boldly tried

to stay his cruel axe, and hindered him;

but Erysichthon, fixing his stern eyes

upon him, said, “Let this, then, be the price

of all your pious worship!” So he turned

the poised axe from the tree, and clove his head

sheer from his body, and again began

to chop the hard oak. From the heart of it

these words were uttered; “Covered by the bark

of this oak tree I long have dwelt a Nymph,

beloved of Ceres, and before my death

it has been granted me to prophesy,

that I may die contented. Punishment

for this vile deed stands waiting at your side.”

No warning could avert his wicked arm.

Much weakened by his countless blows, the tree,

pulled down by straining ropes, gave way at last

and leveled with its weight uncounted trees

that grew around it. Terrified and shocked,

the sister-dryads, grieving for the grove

and what they lost, put on their sable robes

and hastened unto Ceres, whom they prayed,

might rightly punish Erysichthon’s crime;—

the lovely goddess granted their request,

and by the gracious movement of her head

she shook the fruitful, cultivated fields,

then heavy with the harvest; and she planned

an unexampled punishment deserved,

and not beyond his miserable crimes—

the grisly bane of famine; but because

it is not in the scope of Destiny,

that two such deities should ever meet

as Ceres and gaunt Famine,—calling forth

from mountain-wilds a rustic Oread,

the goddess Ceres, said to her, “There is

an ice-bound wilderness of barren soil

in utmost Scythia, desolate and bare

of trees and corn, where Torpid-Frost, White-Death

and Palsy and Gaunt-Famine, hold their haunts;

go there now, and command that Famine flit

from there; and let her gnawing-essence pierce

the entrails of this sacrilegious wretch,

and there be hidden—Let her vanquish me

and overcome the utmost power of food.

Heed not misgivings of the journey’s length,

for you will guide my dragon-bridled car

through lofty ether.” Continue Latin Text

Previous Page Table of Contents Next Page

Tags:

#Epimetheus, #Eros, #Hermes, #Pandora, #Persephone, #Silenoi, #Zeus

Artistic sources edited by R. Ross Holloway, Elisha Benjamin Andrews Professor Emeritus, Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World, Brown Univ., and Frances Van Keuren, Prof. Emerita, Lamar Dodd School of Art, Univ. of Georgia, April 2018.

Literary sources edited by Elena Bianchelli, Senior Lecturer of Classical Languages and Culture, Univ. of Georgia, August 2020

1,285 total views, 1 views today